Economies and markets have had much to contend with in recent years. Back-to-back shocks in the form of pandemic and war have tested policymakers’ grasp on financial stability. For the most part, thus far, the UK economy has been relatively resilient. Far from the rampant unemployment we thought possible as businesses struggled in the face of the forced closure of significant elements of the economy, the labour market is as tight as it has been for many decades. The banking sector, bolstered by stronger capital requirements following the Financial Crisis, has withstood the shock well and is poised to benefit from a rising interest rate environment. The UK housing market has roared back into life despite continued economic uncertainty.

Whilst media coverage of the ‘cost of living crisis’ grows, the average household emerged from the pandemic with a relatively healthy balance sheet. Consumers were largely insulated from the extreme rise in energy prices seen in the winter of 2020-21 by the government’s price cap; the same cannot be said of the large number of energy providers who appear to have deemed hedging an unnecessary expense. As the seasonal nature of energy demand comes to the rescue in the short-term, the outlook for many households’ budgets over the upcoming winter looks more challenging.

Inflation is on everyone’s minds. It is perhaps not surprising that reopening the global economy (with varying degrees of smoothness) has come with frictional pressures. Many economic activities function less like a ‘tap’ that can be turned on and off at will than policymakers may wish. Whilst furlough schemes were partially designed to mitigate the risks associated with losing capacity, some teething issues with firing up industrial activity following an unprecedented shutdown were to be expected. Alongside this, barriers to the free movement of goods and people – both Covid-related and politically induced – have introduced further cost pressure. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back for supply-side cost inflation, but it is not the only factor at play.

We have believed and articulated for some time that a tolerance for higher short to medium-term inflation would prove to be the politically most palatable avenue for reducing the substantial debt burdens introduced by pandemic responses across the developed world. We continue to see this as the case. However, policymakers must walk a fine line between tolerance of short-term pressure and support for an inflationary spiral. With the current labour market tightness and evolving policy response to higher costs of living, inflation has already started to pass through from a ‘transitory’ supply-side shock to the ‘real’ economy. Reversing this trend using dramatic policy tightening without plunging economies into severe recessions is not straightforward. Rapid and substantial interest rate rises would impact not only the already stretched household budget, but also governments’ ability to service debts. Instead, we anticipate a continued gradual tightening of monetary policy towards more ‘normal’ levels and strong rhetoric from Central Banks around the willingness to ‘do whatever it takes’ to regain control of inflation.

In this outlook, we will review the historic corrections and bear markets in an effort to gain context for current market weakness. We will review the current state of the UK economy and look back to previous shocks to help us with possible roadmaps for the coming years. We will conclude with our perceived investment implications for client portfolios.

1. Corrections and Bear Markets

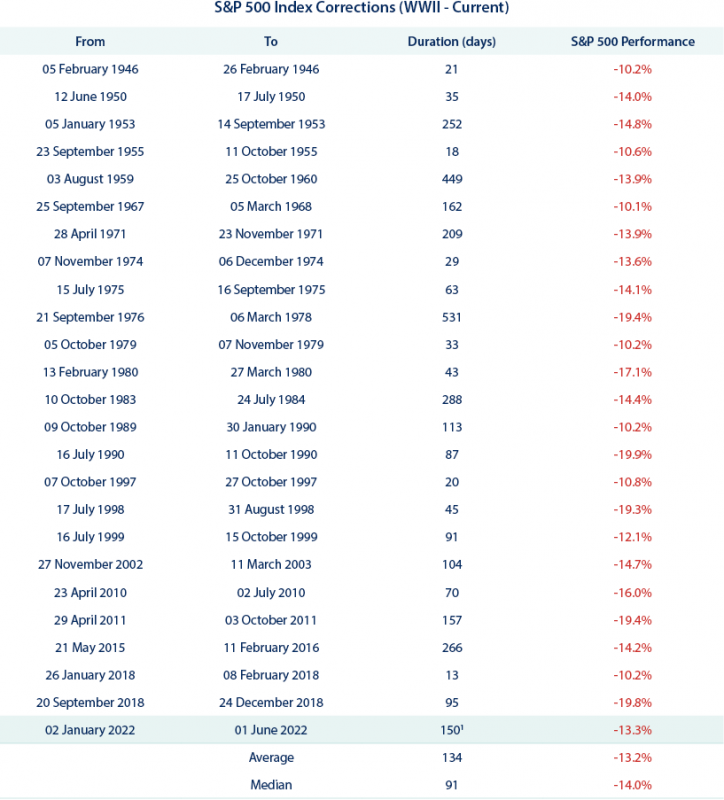

Corrections are part and parcel of stock market investment. They are more common than many people realise and can be protracted and painful for market participants. Consistency of data makes long-term analyses in this area difficult, but the US market can provide some context from as early as the 1940s. Since the Second World War, there have been 24 market corrections (defined as drawdowns of between 10-20%), ranging in duration from under two weeks to nearly 18 months.

Source: updated and re-illustrated from LPL Research, FactSet, Refinitiv.

¹Correction ongoing. All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Performance back to 1950 incorporates performance of predecessor index, S&P 90.

The declines in indices seen since the start of the year remain firmly within the ‘correction’ territory. As is often the case, returns across geographies and sectors have varied significantly. Overall however, this latest bout of volatility is unusual neither in magnitude nor duration. In general, the appropriate response to a market correction is to ride out the discomfort, using the opportunity to reduce the average purchase cost within a portfolio by adding to positions and maintain a long-term horizon.

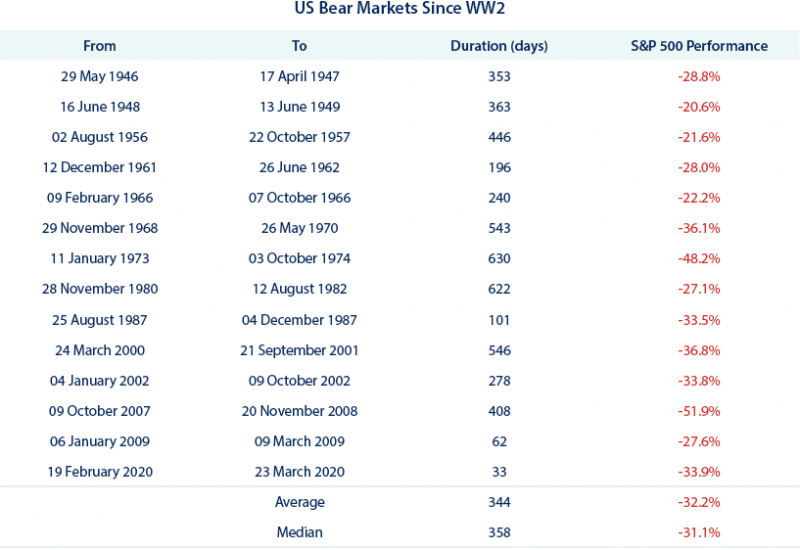

Bear markets, often associated with recessions, are a different proposition. Market drawdowns can be more severe and time to recovery can be (although is not necessarily) protracted. It goes without saying that at some point during every bear market, the market movement would have been classified as a correction.

Source: reproduced from Seeking Alpha, “The complete history of bear markets”, 2022.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Attempting to predict which corrections will evolve into bear markets and which remain as ‘just’ a correction is, in our view, challenging. Instead, we prefer to attempt to prepare portfolios for resilience across a range of market environments. When we compare the current economic climate to that faced in 2018 (the last time we ran this type of analysis), we believe that the probability of a more sustained adverse economic and market environment has risen. The UK and global economies are facing more substantial pressures with less headroom for policy stimulus than they have in recent years. That said, we do not believe that Central Banks will take the decision to rescind easy monetary policy lightly – there is still a long way to go before interest rates reach ‘normal’ levels and we may see supply side cost pressure ease somewhat in the interim.

2. UK Economy – Present and Past

The UK economy rebounded from the Covid shock relatively well, all things considered. Unfortunately, we have faced back-to-back shocks of a magnitude not seen in some time. We remain cautious of over-stating the severity of the current situation – at any point in time there are always concerns which could be highlighted, be they political, social or economic. The UK economy continues to look reasonably stable on many measures, although the situation has undoubtedly deteriorated in recent months.

The UK economy started 2022 in a similar vein to 2021. Growth in Q1 2022 undershot consensus expectations but still came in at a respectable 0.8%. Unemployment edged down to 3.7%, its lowest level since 1974. However, recent Purchasing Manager Indices (‘PMI’s) for May indicate that activity, particularly in the services sector, is starting to slow. Data published by Zoopla in May suggest the housing market is beginning to cool. This sentiment has also been evident in the recent Gfk consumer confidence survey which hit a new low this month, dipping under the level witnessed during the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Growing demand side weakness has been attributed to rising inflation which, in April, hit a 40-year high of 9%. With the energy price cap expected to rise by 32% in October, inflationary pressure is unlikely to abate in the short-term.

Although demand side pressures on prices are showing signs of abating, supply side pressures continue. In the UK there are currently fewer unemployed people than there are job vacancies. This has put pressure on wages, with weekly earnings now up 7% year on year. Nevertheless, a wage-price spiral like the one seen in the 1970s seems unlikely given the diminished size and power of trade unions today. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine and restrictive Covid policy in China continue to provide supply-side pressure which is difficult for UK policymakers to counterbalance.

Early in 2022, sentiment towards the British pound was positive. Although inflation was rising, the Bank of England (‘BoE’) was credited for raising interest rates earlier than other major Central Banks. As the situation has evolved however, market consensus has moved towards a more bearish stance for Sterling. Some commentators have been critical of the relatively modest pace of tightening employed by the BoE. Consequently, the Pound has fallen against most other major currencies and 10% against the Dollar. With inflation higher than in most other developed countries and the consumer outlook deteriorating, the BoE now risks tipping the economy into recession as it seeks to achieve its mission of price stability.

Whilst the UK economy is facing significant inflationary pressure with few signs of relief, we remain some way from the economic trials of previous recessionary periods. We discussed previous shocks to the UK economy in our Outlook of October 2018 as UK investors grappled with the consequences of Brexit. We update this analysis below:

1970s: Stagflation, Sterling Depreciation and Stock Market Volatility

Britain joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in January 1973, having twice been denied membership during the 1960s. One implication of membership was the introduction of the Common Agricultural Policy on UK farmers. This supported farmers with higher food prices leading to ‘cost of living’ inflation. At the same time, Arab oil-producing nations were reacting to the perceived Western support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, leading to the imposition of an oil embargo in October 1973. Oil prices had quadrupled by the time the embargo was lifted (from $3 to $12/bl), putting pressure on transport costs and the manufacturing sector. Trade Unions were also proving politically and economically problematic, with Miners’ Strikes in particular having a severe impact. The Conservative government of Edward Heath was forced to introduce a three-day working week in January 1974 before facing defeat by Harold Wilson’s Labour party the following month.

The economic impact of this series of events was severe. The UK faced fourteen consecutive quarters of recession in 1973-5, with overall GDP declining by 3.9%. Unemployment remained high throughout the period, peaking at 9% in May 1975. Inflation exceeded 24% in 1975, despite interest rates remaining at 12-14% throughout the recession. Sterling depreciated by over 30% between 1971 and 1977.

Contrasting this period with the situation in the UK today demonstrates the relative stability that the UK still enjoys. Although GDP growth has slowed moderately in recent years, we have enjoyed long periods without sustained recession. The Global Financial Crisis initiated five consecutive recessionary quarters, the most since the 1970s. Inflation had, until 2022, been relatively stable, peaking at 4.8% in September 2008 and remaining between 0-3% between 2012 and 2021. Over the last six months, we have seen this rise to 9% with signs of continued pressure. Unemployment in contrast, has been steadily declining, now sitting at record lows of under 4%. Sterling has been volatile, falling from its modern peak of >$1.70 in July 2014 to a low of $1.16 in March 2020. The recovery to >$1.40 in mid-2021 was short-lived as pressure on Sterling mounted in February – April 2022, bringing us to a current level of $1.23-$1.27. A depreciating currency tends to add inflationary pressure to a net importing nation like the UK – pressure policymakers could do without at the current time.

1990s: Black Wednesday, Currency Crisis and the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM)

A booming UK economy in the mid to late-1980s was accompanied by high levels of inflation. In Europe, countries were moving towards the goal of a currency union, with Italy, France and Spain tying their currencies to the German Deutschmark. Believing that a pegged currency could bring inflation under control, the UK joined the ERM in October 1990. By September 1992, the divergence between the UK and German economies left Sterling at the lower limit of the ±6% band. Speculators, most famously George Soros, started buying UK Gilts with the intention to sell them back to the Bank of England before buying again at a lower price. John Major raised interest rates from 10% to 12%, then to 15% in one day. The move was not enough, and the UK crashed out of the ERM on 16 September 1992.

The eventual impact of these events was overwhelmingly positive for the UK economy. Sterling depreciated c.35% against the dollar over six months, leading to a major economic recovery. The ‘Great Moderation’ period followed, with the UK experiencing 63 consecutive quarters of positive economic growth. The UK’s experience of the ERM was not a positive one. It demonstrated the challenges of tying divergent economies together. It could be argued that the European Sovereign debt crisis of 2010-11 was another example of such challenges. Southern European economies remain structurally different from those of Northern Europe. Without full fiscal union, monetary union remains difficult, as evidenced by continued political unrest across Europe.

Conclusions on the UK economy

In 2018, we concluded that the UK economy remained strong and able to withstand a significant shock in the way that it was not able to in the 1970s. Thus far, this conclusion has proved correct; the Covid shock (and associated frictions), followed immediately by significant conflict, have tested UK economic resilience. It is encouraging to see how well these issues have been navigated thus far. Inflation provides the biggest challenge for policymakers going forward, but we continue to believe that the UK financial system remains relatively well-positioned to tackle a short-medium term shock.

Investment Implications

Our proposed amendments to portfolios continue to evolve in line with those discussed in previous Outlooks. As inflation rises, the cost associated with holding traditional safe haven investments rises too. Bond markets continue to look challenged but some allocation remains justified in any ‘all-weather’ portfolio. We look to index-linked and non-Sterling denominated bonds to provide some diversification in this space. We also continue to look at Alternatives, including Property, Infrastructure and Absolute Return/Macro strategies to help provide balance.

Within the equity space, we have been rebalancing away from the higher valued parts of the market and adding exposure to strategies focussing on quality at a reasonable price. We continue to hold significant positions in Asia. Many developed and emerging Asian markets have seen significant rotations and falls, in line with or exceeding Western peers. Although it is uncomfortable to be on the receiving end of this type of drawdown, we believe that the long-term principle of geographical diversification remains intact. Fundamentally, some of these economies look to be in better shape than those in the West and we are encouraged by a recent renewal in investor interest in these areas.

We retain exposure to small and mid-cap companies despite drawdowns, believing that over the long-term it will be these names driving wealth and value creation. Although personal savings rates have returned towards pre-pandemic levels in most regions, households remain in a position of relative fiscal strength due to lockdown savings and furlough support. In the absence of significant business failures and an associated rise in unemployment, we are hopeful that economies will continue to weather the uncertain times ahead. We continue to see high quality companies punished by nervous investors and encourage clients to focus on the potential opportunities arising in this market environment.

As always, our Investment Committee endeavours to be responsible in all investment decisions and seeks only to select investments which are in the best interests of clients. We are committed to the highest standards of research and insist on the same standards where external fund managers are recommended. The processes, policies and procedures of fund managers form a central part of our analysis of external managers and we will continue to assess potential investments across a wide range of quantitative and qualitative criteria.

Risk warnings

This document has been prepared based on our understanding of current UK law and HM Revenue and Customs practice, both of which may be the subject of change in the future. The opinions expressed herein are those of Cantab Asset Management Ltd and should not be construed as investment advice. Cantab Asset Management Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. As with all equity-based and bond-based investments, the value and the income therefrom can fall as well as rise and you may not get back all the money that you invested. The value of overseas securities will be influenced by the exchange rate used to convert these to sterling. Investments in stocks and shares should therefore be viewed as a medium to long-term investment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. It is important to note that in selecting ESG investments, a screening out process has taken place which eliminates many investments potentially providing good financial returns. By reducing the universe of possible investments, the investment performance of ESG portfolios might be less than that potentially produced by selecting from the larger unscreened universe.